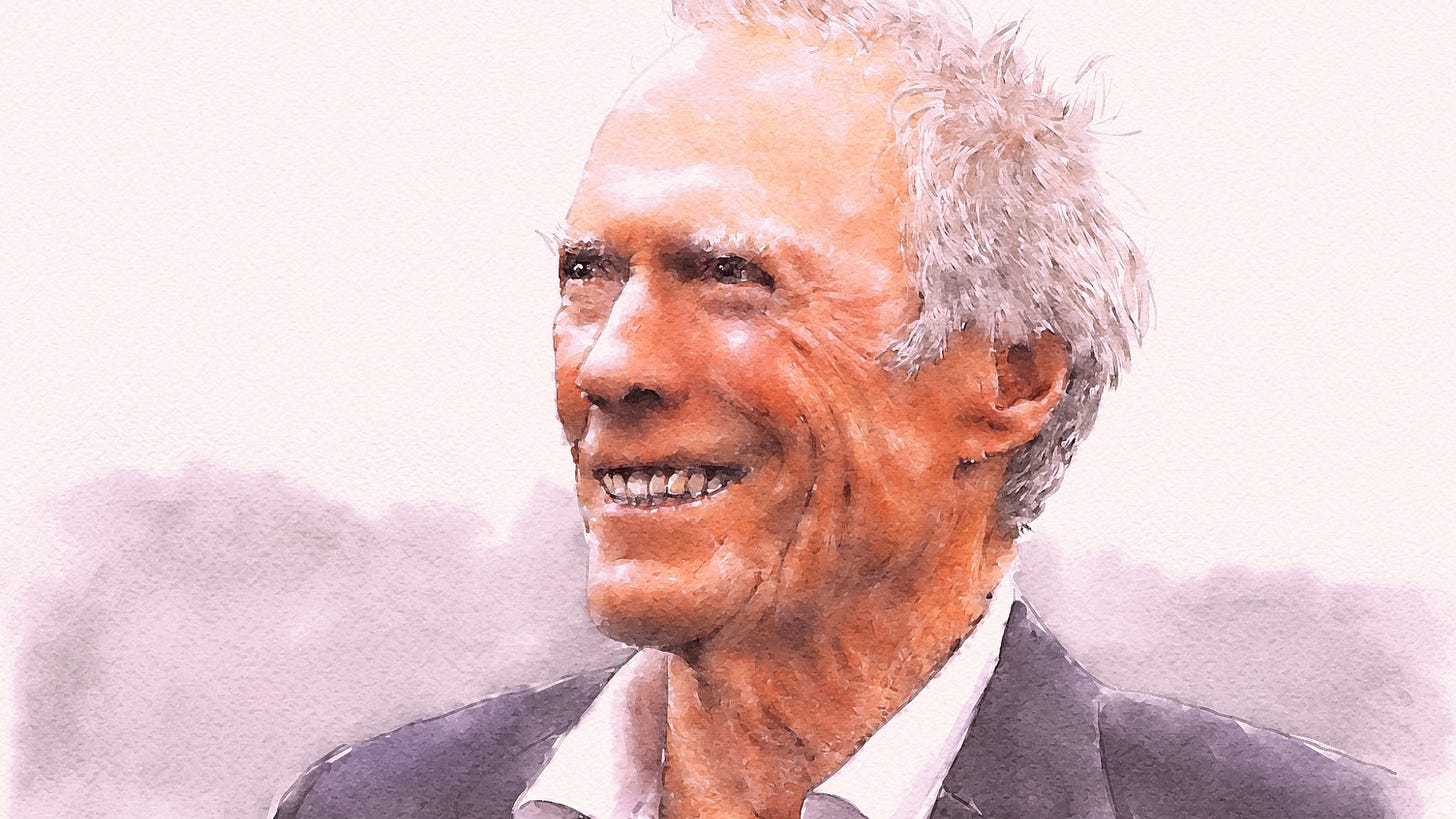

Un/Forgiven: An Open Letter to Clint Eastwood

“It’s a hell of a thing, killin’ a man”

I had an opportunity to visit California this past summer, and among other places I spent a couple of days in Carmel-by-the-Sea. Carmel’s most famous resident is actor-director—and one-time mayor—Clint Eastwood. I decided to write Clint an open letter.1

Dear Mr. Eastwood:

Hello. I’m a fan of yours, but this isn’t an ordinary fan letter. And I’m aware that this is a sad time for you: although I wouldn’t expect you to dive into fan mail right now, I’m hoping that, just maybe, you’ll eventually read this.

Let me start by offering my condolences on Christina’s passing. I have no doubt that, as your daughter Morgan said, this is a “devastating loss for [y]our whole family.” While I can’t say I know how you feel, I do know that I would be likewise devastated if I lost my wife.

It’s being reported that

concerns over Eastwood’s health have intensified. Sources close to the ‘Dirty Harry’ star have noted a noticeable decline in his physical condition in recent years. . . . Friends and family have expressed worry about his increasing reclusiveness and diminishing energy. . . . An insider shared that the actor no longer seems like himself and spends much of his time secluded in his Carmel home.2

Mister Eastwood, I sincerely hope you’ll give some consideration to the following.

Facing death

Death sucks. But if there’s a positive side to it, maybe it’s that it prompts us to revisit life’s big questions: What is life about? Is there anything beyond? And if there is—can I know it?

“Revisit” is an appropriate word, because you’ve pondered such questions before. I don’t know your thought process or if you’ve come to any conclusions, but in a way, you’ve sort of become a fourth viewpoint character in your own film Hereafter; or the star of a sequel, if you like.

Of course, you don’t like. None of us does. But the journey’s unavoidable. At one point in Hereafter, Billy quotes another character as saying: “A life that’s all about death is no life at all.” There’s some truth to that; after all, why go through life being morose and morbid? And yet . . . pondering death frequently—and not just abstractly, but personally: I’m going to die—is spiritually healthy.

Multiple cultures recognize this. For example, “The country of Bhutan has made it part of its national curriculum to think about death anywhere from one to three times daily,” and yet “extensive studies conducted by Japanese researchers have found that Bhutan is among the world’s 20 happiest countries.”3 “Buoyed by research like this there are [Western] social movements, such as so-called Death Cafés and the Death Salon collective, that provide space for people to meet and talk openly about death.”4

Now, the author of the previous quote poses this question: “So, are we in the West thinking about death wrong? I would argue, no. Because there’s no ‘wrong’ way to do it.” I strongly disagree. As with any other subject, we can entertain right or wrong ideas about death; come to right or wrong conclusions.

Another writer, for instance, has argued that pondering death furnishes a different perspective on life. She’s certainly right about that, but I have to challenge the reductionistic perspective at which she arrives: “Nothing helps you enjoy the present more than accepting its end.”5 That’s true—but I submit that squarely and honestly facing death will, ideally, prepare us for what comes after.

The same author goes on to say that when you have a healthy view of death, “[y]ou’re only scared of the right things.” Again, I have a measure of agreement with her—but once more she narrows the scope of her gaze to this life only:

Once you’ve accepted the scariest part of life, everything else just seems like a walk in the proverbial park. The idea that your life will end—that you will leave everything you know and love—is as liberating as the idea that none of it really matters.

Mister Eastwood, I don’t know about you, but I don’t find that liberating; I find it dismal. It’s the same outlook as the nihilism of old: “Let’s feast and drink, for tomorrow we die!” (Isaiah 22:13) “Eat, drink, and be merry!” (Luke 12:19)

To such people Jesus Christ says: “You fool! . . . Yes, a person is a fool to store up earthly wealth but not have a rich relationship with God.” (Luke 12:20-21)

Which leads me back to Hereafter: the great irony in Billy’s statement is that he’s talking to a character named Christos. Since the film involves the notion of communicating with the dead, I feel compelled to ask: What if you could hear from someone who died and came back—the real “Christos”?

Christ and masculinity

You’ve long been “one of the enduring embodiments of American masculinity[.]”6 Indeed,

the closest thing that American men have to a patron saint right now is Clint Eastwood. . . . During all the real and imagined crises of American masculinity that the past half century has coughed onto our screens, Eastwood has been the one stable figure in the midst of the darkness and the turmoil . . . . Eastwood’s endurance is the endurance of saints, and what he embodies more than anything is the definitive virtue for American men both then and now: restraint. He rides the line between his own terrible desires and the world as it is with the grace we all aspire to.7

Mister Eastwood, do you know what that actually makes you? I’m not being melodramatic when I say that this makes you, in part, a reflection of the Perfect Man. Jesus himself:

Though he was God, he did not think of equality with God as something to cling to. Instead, he gave up his divine privileges; he took the humble position of a slave and was born as a human being. When he appeared in human form, he humbled himself in obedience to God and died a criminal’s death on a cross. [Philippians 2:6-8]

I’ve been told restraint is “sexy.” (I need to bear this in mind when I’m about to scarf down some junk food that I should stay away from.) But restraint is also Christlike. Even though Jesus has “been given all authority in heaven and on earth” (Matthew 28:18) and “will someday judge the living and the dead” (2 Timothy 4:1), nonetheless at the present time he shows restraint, because he came “to liberate the world, not to judge it.” (John 12:47).

The Jesus who conquered death is the same Jesus who wept over it (John 11:35). He embodies the perfect balance of power and compassion. He loves you and cares about what you’re going through.

The thing is, though, “if we took care to judge ourselves, then we wouldn’t have to worry about being judged by another” later on (1 Corinthians 11:31). Here again, Mr. Eastwood, it seems to me that you’re an illustration of a Biblical truth.

If Eastwood embodies a certain brand of American masculinity, he has also thoroughly explored it.8

However, in the latter half of Eastwood’s lengthy career, much of his work both as an actor and a director has been deconstructing the tropes he was known for and subverting that macho image he cultivated in his earlier years.9

May I offer a suggestion? What if you explored the Paragon of masculinity—and “deconstructed” your cinematic legacy at a much deeper level by comparing/contrasting yourself with Him? If you were to venture down that path—strange at first, to be sure—you might just find deconstruction morphing into re-construction: “in everything”—including heartbreak—”God works for the good of those who love him . . . that they would be like his Son.” (Romans 8:28-29)

“Dustin Hoffman and Al Pacino play losers very well,” you were quoted as saying in the ‘70s. “But my audience likes to be in there vicariously with a winner.”10 You’re spot-on—and thanks for yet another spiritual illustration. We all want to be “winners,” however that’s defined; many of us think we’re “winners” even when we’re not. This is nowhere more true than in man’s spiritual assessment of himself: we’re loath to admit it, but the reality is that, compared to Jesus, we’re all losers. “All of us have sinned and fallen short of God’s glory.” (Romans 3:23)

Ironically, the acknowledgment that your fans want “to be in there vicariously with a winner” points to the Good News about Christ: he’s the Ultimate Winner—“I have overcome the world.” (John 16:33)—who represents us in his death and resurrection.

In fact, Christianity is all about vicariousness. Jesus “suffered once for sins, the just for the unjust, to bring you to God” (1 Peter 3:18). And the one who believes this Good News can then say, “My old self has been crucified with Christ. It is no longer I who live, but Christ lives in me. So I live in this earthly body by trusting in the Son of God, who loved me and gave himself for me.” (Galatians 2:20)

This new life is a shift from . . .

Unforgiven to forgiven

In what is certainly one of your best films, Unforgiven, your starring character, gunslinger Bill Munny, opines, “It’s a hell of a thing, killin’ a man. Take away all he’s got and all he’s ever gonna have. . . . We all have it comin’, kid.” Munny’s pretty blasé in that scene, but later on he thinks he’s close to death himself, and the grim reality hits: “I seen the angel of death. . . . I’m scared of dyin’.”

Fearful of the dark legacy he’ll leave behind, he pleads with Morgan Freeman’s Ned Logan, “Don’t tell nobody—don’t tell my kids . . . none of the things I done.”

Okay, that’s Munny’s kids—but what does he expect for himself? Nothing positive, that’s for sure. When the gunslinger corners one of his targets, the man’s last words are: “I’ll see you in hell, William Munny”—who can only answer: “Yeah.”

What’s your own expectation, Mr. Eastwood? Are you, too, “scared of dyin’”? If you are, here’s something for you to consider: “the man who hears what I have to say and believes . . . does not have to face judgment; he has already passed from death into life.” (John 5:24)

You can go from unforgiven to forgiven.

And you’re in an appropriate place to do it too: a town that owes its name to Mt. Carmel in Israel. That mountain was the scene of a showdown between Yahweh, the one true God, and the false god Ba’al. In the presence of hundreds of witnesses, most of whom were idol-worshippers, God proved Himself infinitely superior to any challenger; to anyone or anything we might exalt above Him.

I think He wants another “Carmel showdown,” Mr. Eastwood. Mind you, a lot less “cinematic,” but also much closer to home. Not just Carmel-by-the-Sea, but in your own heart.

And while I certainly don’t want you to be “all about death,” at the same time it’s important that you (and all of us) give some thought to it, for the simple reason that “people are destined to die once, and after that to face judgment” (Hebrews 9:27). According to the Bible, that judgment has been entrusted to God’s Son.

Why not face it now rather than later?

Because if you face it now, right now, before it’s too late—“How will I be judged?”—then you won’t need to face it later. It’s a daunting, self-undoing question, but the Lord has made you this promise: “anyone who trusts in me will not be disappointed.” (Isaiah 49:23)

Ironically, such a faith requires a type of “suicide”: “Those who belong to Christ Jesus have crucified their sinful self. They have given up their old selfish feelings and the evil things they wanted to do.” (Galatians 5:24)

As Bill Munny might say, “It’s a hell of a thing, killin’ yerself.” But I can tell you from firsthand experience, it’s entirely worth it. And beyond this life, “No eye has seen, no ear has heard, and no mind has imagined what God has prepared for those who love him.” (1 Corinthians 2:9)

Now that would really “make your day,” Mr. Eastwood. “That ain’t bad, considerin’.” (Bill Munny)11

Dig deeper:

†

He’ll likely never see this, of course—which is why I actually mailed him a version of this.

“Concerns for Clint Eastwood’s Well-Being Emerge Following Partner Christina Sandera’s Death,” Marca.com (22 July 2024).

Michael Easter, “The Secret to Happiness? Thinking About Death,” Outside (13 May 2021).

Jules Howard, “Why it’s healthy to think about your own death,” BBC: Science Focus (26 Oct. 2021).

Lauren Martin, “9 Reasons Why People Who Constantly Think About Death Are More Alive,” Elite Daily (24 Mar. 2015).

Darren Mooney, “Clint Eastwood Has Spent Decades Embodying and Exploring American Masculinity,” The Escapist (1 June 2020).

Stephen Marche, “Why Is Clint Eastwood Still the Man?“ Esquire (20 Oct. 2010).

Mooney, ibid.

Michael Hagerty, “The Bigger Picture: Clint Eastwood And The Reconsideration Of Masculinity,” Houston Matters (23 Sept. 2021).

Mooney, ibid.

David Webb Peoples, The William Munny Killings (Original Screenplay, 23 Apr. 1984).