In 2018 I got some very sad news: someone I have long admired “came out” as an atheist: “Batman doesn’t believe in God . . . at least not in a traditional sense. The revelation comes at the conclusion of comic writer Tom King's . . . Batman #53.”1

Well, although I was disappointed—anyone who knows me knows I’m a Bat-fan!—I can’t say I was surprised. For one thing, the Batman comics have been predominantly written by secular/non-Christian authors—although they used to side-step overt discussions of religion. What’s more, it’s not uncommon for real-world people to abandon God in the wake of severe suffering. For example, many Jewish survivors of the Holocaust converted to atheism—so is “half Jewish” writer Tom King an atheist?

Not necessarily:

In any case, back in the comic-book realm, 8-year-old Bruce famously witnessed his parents gunned down in Crime Alley. He’s been haunted by that traumatic memory ever since, and upon reaching adulthood he commenced fighting crime night after night as Gotham City’s Caped Crusader—thus exposed for decades to society’s underbelly of the criminal, the corrupt, and the crazed. In this fictional context it all seems very melodramatic—until you consider the parallel experiences of big-city police officers, or war veterans.

One thing Bruce Wayne hasn’t abandoned, though, is his deep sense of justice, and the drive to see it manifested in his city. “I am an instrument of justice,” he declares.2

This gives us insight into Bruce’s conscience; as he puts it himself, “No man is perfect . . . but every man should strive to be.”3 And reflecting on his mission as a crimefighter, he observes that “a hero is not bound by sentimentality or the vagaries of public opinion. A hero is held to a higher standard of truth and justice.”4

Question: How does an atheist (or anyone else) intuit that “higher standard”? How does any of us recognize “right” from “wrong”?

C. S. Lewis described a crucial factor in his shift from atheism to Christianity:

My argument against God was that the universe seemed so cruel and unjust. But how had I got this idea of just and unjust? A man does not call a line crooked unless he has some idea of a straight line. What was I comparing this universe with when I called it unjust?5

So here’s the thing: Bruce Wayne is the kind of person who knows he lives in a moral universe, and that people in this universe don’t always do what they ought. But where did the “ought” come from? If the universe is here by accident, as atheists believe, then how did an accident produce “oughts”?

In Bruce’s own case, it seems he had a quasi-Christian upbringing before his parents were murdered: there’s ongoing discussion among Bat-fans (and writers themselves) as to whether he “is a mostly lapsed Catholic or a mostly lapsed Episcopalian.”6 Comic-book writer Chuck Dixon, himself a Christian, has said that Bruce “must be Catholic. No Protestant ever suffered guilt the way Bruce does.”7 Given such a background along with his superlative intellect, it’s not a shock to hear Batman channeling his inner St. James when he confronts the corrupt among Gotham’s wealthy: “Ladies. Gentlemen. You have eaten well. You’ve eaten Gotham’s wealth. Its spirit. Your feast is nearly over. From this moment on—none of you are safe.”8

But this begs two questions: (1) Who or what defines “justice”? And (2) How are we aware of it?

To answer the first question, I’d suggest turning to the Bible’s most offensive verse: “In the beginning God created the heavens and the earth.” (Genesis 1:1) Why is this “most offensive”? Quite simply: because everything else that non-Christians don’t like in the Bible follows logically and inevitably from Genesis 1:1. As Christian apologist Greg Koukl has put it:

The basic principle is a commonsense one: If you make it, it’s yours. . . .

Since God made everything out of nothing, it all belongs to him. He has proper authority to rule over all because none of it would exist without him. That includes you and me . . . . We don’t own ourselves—God does.9

The logical implication is that the Creator and Owner of the universe is the only One who gets to define “right” and “wrong.” Nobody else.

The logic would be the very same if atheism were true: if mindless Nature produced us and everything we see around us—then mindlessness would get to define morality. Ah, but since it’s logically impossible for mindlessness to define anything at all, morality would then be undefined. Indeed, the very term “morality” would be a meaningless word; a word not even invented.

Yet we know intuitively that morality is not undefined or meaningless. We know intuitively that some things are just right, and some things are just wrong.

Okay, so how do we know? This second question is also answered within the pages of Scripture, this time by the Apostle Paul:

Those who are not Jews do not have the [Old Testament] law, but when they freely do what the law commands, they are the law for themselves. This is true even though they do not have the law. They show that in their hearts they know what is right and wrong, just as the law commands. And they show this by their consciences. Sometimes their thoughts tell them they did wrong, and sometimes their thoughts tell them they did right. [Romans 2:14-15]

Human beings have a conscience, a moral compass. And since—as we saw from the “most offensive verse in the Bible”—we didn’t create ourselves, this means God’s the One who implanted the human conscience. We are designed to intuit right from wrong. This doesn’t mean our conscience is perfect, requiring no moral education; the Bible itself (not to mention our own experience) is abundantly clear that we live in a fallen world in which we ourselves are spiritually damaged. That damage includes our capacity to make moral judgments.

But broadly speaking, the human race collectively possesses a moral intuition that reflects its Creator’s own character.10 This fact also follows logically and inevitably from Genesis 1:1.

Conversely, if atheism were true, then humans—assuming we existed at all!—would be wired by evolutionary forces to behave instinctively in ways that propagate the species. Propagation of the species would be the only evolutionary imperative; questions of objective “right” and “wrong” would be absolutely meaningless.

But again: we know intuitively that this isn’t the case. Ergo, atheism cannot be true.

I’d love to write a story in which Batman crosses paths with real-world homicide detective J. Warner Wallace, owner-author of the website Cold Case Christianity.11 Perhaps the two could have a long conversation, or a series of conversations, about the divine trail of clues that should lead the “world’s greatest detective” to the utterly rational conclusion that, yes, God does exist.

Of course, it’s always possible that, somewhere, at some time, in the DC universe, Bruce and his ward and fellow crimefighter Dick Grayson—Robin—have had just such a conversation. Dick has often served as a constraint on Bruce’s propensity for brooding and violence, and it’s just possible, albeit strictly theoretical, that the younger man is a Christian.12 If so, who’s to say he hasn’t ever witnessed to Bruce! All I know is, we gotta get Batman saved!

Wait . . . did I just say that? . . . Sorry, my superhero geekdom got the better of me.

Here’s the reality, though: if I were witnessing to someone like Bruce Wayne, I’d talk about justice—as well as his sense of mercy. Despite the fact that Batman once told a villain, “You demand mercy? I have only justice”13—nonetheless, the Dark Knight’s pattern has been to expose at least a small degree of mercy’s light, such as in his traditional refusal to use a gun.

He once even went so far as to tell his arch-enemy the Joker:

“I don’t want to hurt you. . . . It doesn’t have to end [in death]. I don’t know what it was that bent your life out of shape, but who knows? Maybe I’ve been there too. Maybe I can help. We could work together. I could rehabilitate you. You needn’t be out there on the edge anymore. You needn’t be alone. We don’t have to kill each other. What do you say?”14

And to his on-off ally Helena Bertinelli, alias Huntress: “You want vengeance. I don’t.”15

I would want to tell someone with that sort of moral awareness: Mercy and justice have met at the cross of Jesus Christ, who paid for our sins in order to satisfy both the love and the justice of a holy God. To someone who recognizes and is willing to admit, as Bruce Wayne has, that “deep down, I’m not” “essentially a good person,”16 I’d want to say: You are in exactly the right position to perceive and receive the truth of the Gospel. For “Christ Jesus came into the world to save sinners” (1 Timothy 1:15), and “if we confess our sins to him, he is faithful and just to forgive us our sins and to cleanse us from all wickedness.” (1 John 1:9)

Returning to the author of Batman #53, we discover that an “atheistic” Caped Crusader isn’t necessarily what King had in mind:

Turns out there’s another possible interpretation of this story—and it links the fictional crime-fighter to every single real-life human being. Movieweb’s Trevor Norkey is right when he says “that Bruce Wayne used to believe in a higher power, but no longer does.”17

Yet is that “higher power” the God of the Bible . . . ?

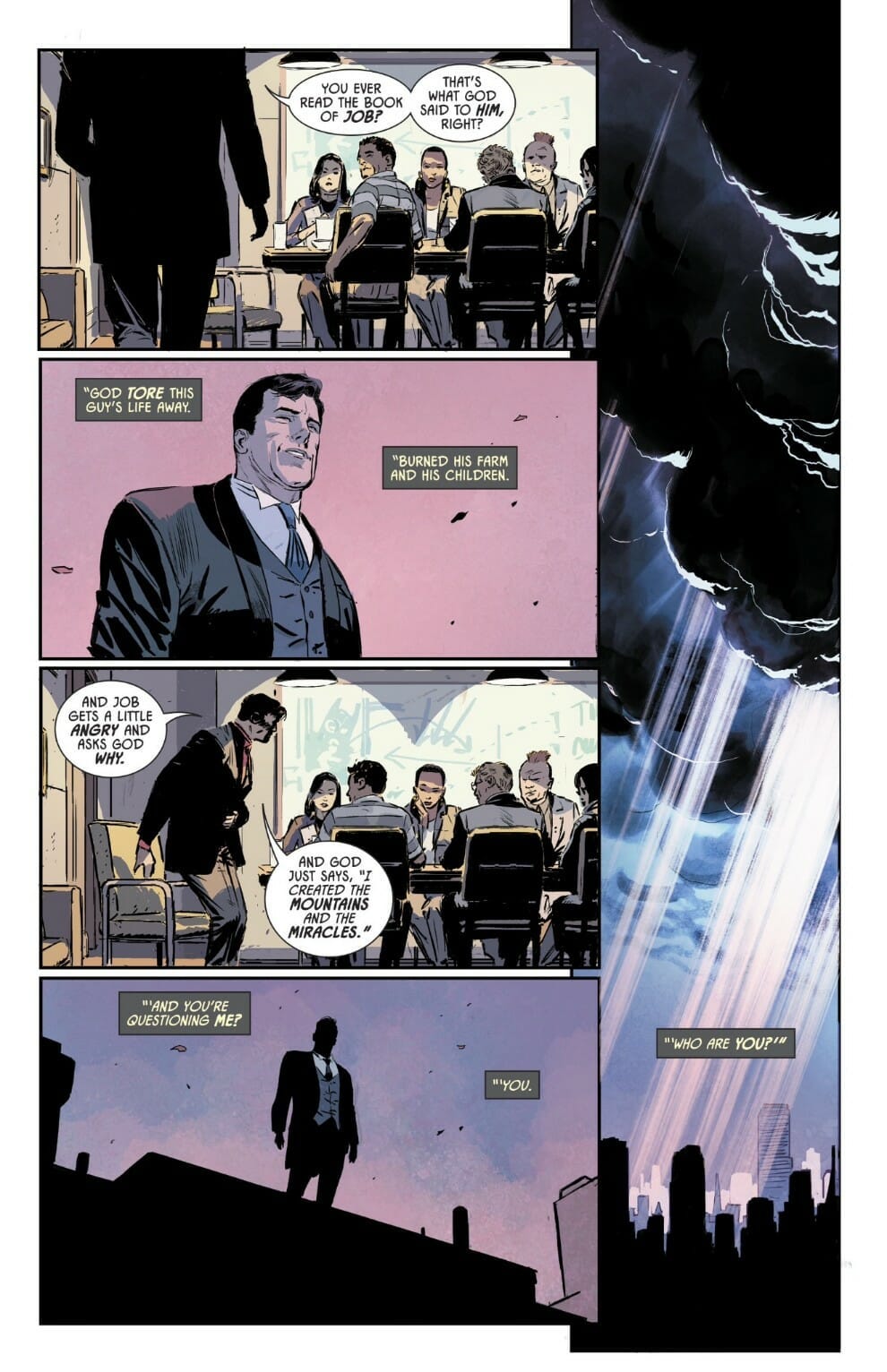

When Bruce Wayne is unexpectedly called to jury duty, it develops that “the trial has forced him to go against the evidence Batman found to make [the defendant] look guilty.”18 The approach Bruce takes in reasoning with his fellow jurors is quite surprising, coming from an alleged “atheist”:

What a question when confronted by God—striking you in the heart like a celestial arrow. How would you answer that question? . . . Who do you think you are?

It seems that this was the very question unexpectedly hitting Bruce Wayne’s conscience, almost as if he sensed that he was being confronted by his Maker. As he reasons this out for the other jurors—who appear ready to accept Batman’s judgment, thus ceding their duty to an unaccountable, costumed vigilante—he hints at the tug-of-war going on in his soul.

The “higher power” in which Bruce once believed is . . . himself. He had said earlier that “God is above us. And he wears a cape”—subsequently realizing that he’d begun to view himself, even if unconsciously, as an infallible detective and as having the power of judgment over criminals.

But infallibility and judgment belong to God alone.

And so, with an identity as “God” now off the table, Batman now has some real soul-searching to do.

There’s a wonderful irony here: Bruce Wayne has become an “atheist” in the same sense the early Christians were. Yes, you read that correctly: the early Christians. For that’s what their Greco-Roman neighbors accused them of:

As the second-century Christian apologist Athenagoras states, early Christians were accused of three crimes: cannibalism, incest, and atheism.

All three were serious charges, but here I would like to discuss one which perhaps seems strangest to our modern ears: atheism. This was perhaps the oldest charge laid against the Christians, with hints of it being found in the New Testament itself (ex., Acts 19:23ff.) and clear attestation found in the early second century at Polycarp’s martyrdom.19

As all of us must, Batman realizes that God is God, and we are not.

Although this fictional character is handled by different authors in different comic-book stories, I like to imagine them all as touching on a “real” Batman somewhere out there. And so, when in Batman #53, Bruce Wayne finds himself duly humbled, I like to think he’s just turning back to the same awareness of God, however dim, that he had when he prayed for himself and his allies “on the outskirts of Jerusalem. . . . Yes, I prayed. . . . It focuses the mind.”20

And on another occasion he expressed hope in a rather Christian-sounding destiny: “Good versus evil. The eternal struggle ends here . . . in the eternal city.”21 That sounds suspiciously like Revelation 21-22. Preach it, Bats! “You are not far from the Kingdom of God.” (Mark 12:34)

Derek Stauffer, “Batman is An Atheist, DC Comics Confirms,” Screen Rant (15 Aug. 2018) (accessed 3 Oct. 2021).

Chuck Dixon (writer), “The Grieving City,” Detective Comics Vol. 1 no. 724 (Burbank, CA: DC Comics, Aug. 1998), quoted in the DC Database (accessed 22 Aug. 2018).

Doug Moench (writer), “Hell to Pay,” Batman Vol. 1 no. 546 (Burbank, CA: DC Comics, Sep. 1997), quoted in the DC Database (accessed 22 Aug. 2018).

Larry Hama (writer), “Positive Role Model,” Batman: Shadow of the Bat Vol. 1 no. 90 (Burbank, CA: DC Comics, Oct. 1999), quoted in the DC Database (accessed 22 Aug. 2018).

C. S. Lewis, Mere Christianity (New York: HarperCollins, 2015 [orig. 1952]), 38 (italics orig.).

“The Religious Affiliation of Comic Book Character Bruce Wayne/Batman,” Adherents.com (30 Nov. 2005; modified 20 Aug. 2007; © 2014) (accessed 22 Aug. 2018).

Ibid.

Frank Miller (writer), Batman: Year One (Burbank, CA: DC Comics, 1987); quoted in “Batman (comics),” Wikiquote (accessed 21 Aug. 2018). Compare James 5:1, 3, 5-6.

Gregory Koukl, The Story of Reality (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 2017), 44-45. Lewis argued similarly: “If somebody else made me, for his own purposes, then I shall have a lot of duties which I should not have if I simply belonged to myself.” (Mere Christianity [ibid.], 75)

The universal nature of this moral intuition—it isn’t restricted to a given era or culture—is amply demonstrated by C. S. Lewis in his essay “Illustrations of the Tao,” the appendix to his book The Abolition of Man (New York: HarperOne, 2001, 2015; orig. 1944), 83-102. Lewis gives samplings of the ethics and law-codes of various cultures down through history, showing their remarkable similarities on major themes.

From his “About the Author” page: “J. Warner Wallace is a cold-case homicide detective, popular national speaker and best-selling author. He continues to consult on cold-case investigations while serving as a Senior Fellow at the Colson Center for Christian Worldview. He is also an adjunct professor of apologetics at Biola University and a faculty member at Summit Ministries.”

See “The Religious Affiliation of Chuck Dixon[,] comic book writer,”Adherents.com (7 Jan. 2006; © 2014) (accessed 26 Aug. 2018).

John Ostrander (writer), “Grotesk,” Batman Vol. 1 no. 662 (Burbank, CA: DC Comics, Mar. 2007), quoted in the DC Database (accessed 22 Aug. 2018).

Alan Moore (writer), Batman: The Killing Joke (Burbank, CA: DC Comics, 1988); quoted in “Batman (comics),” Wikiquote (accessed 21 Aug. 2018).

Dennis O'Neil (writer), “The Witness,” Azrael: Agent of the Bat Vol. 1 no. 65 (Burbank, CA: DC Comics, June 2000), quoted in the DC Database (accessed 22 Aug. 2018).

Jeph Loeb (writer), “The Battle,” Batman Vol. 1 no. 612 (Burbank, CA: DC Comics, Apr. 2003); quoted in the DC Database (accessed 22 Aug. 2018).

Trevor Norkey, “DC Confirms Batman Is an Atheist,” Movieweb (Aug. 17, 2018) (accessed 19 Aug. 2018; italics mine).

Kevin Lainez, “Batman #53 Review,” Comic Book Revolution (20 Aug. 2018) (accessed 7 Oct. 2021).

Andrew Messmer, “Christians are Atheists,” Evangelical Focus Europe (25 Apr. 2020) (accessed 7 Oct. 2021).

Roger Stern (writer), “No Other Gods Before Me!”, JLA Classified Vol. 1 no. 53 (Burbank, CA: DC Comics, Apr. 2008), quoted in the DC Database (accessed 22 Aug. 2018).

Matteo Casali and Brian Azzarello (writers), “Rome,” Batman: Europa Vol. 1 no. 4 (Burbank, CA: DC Comics, Apr. 2016), quoted in the DC Database (accessed 22 Aug. 2018).