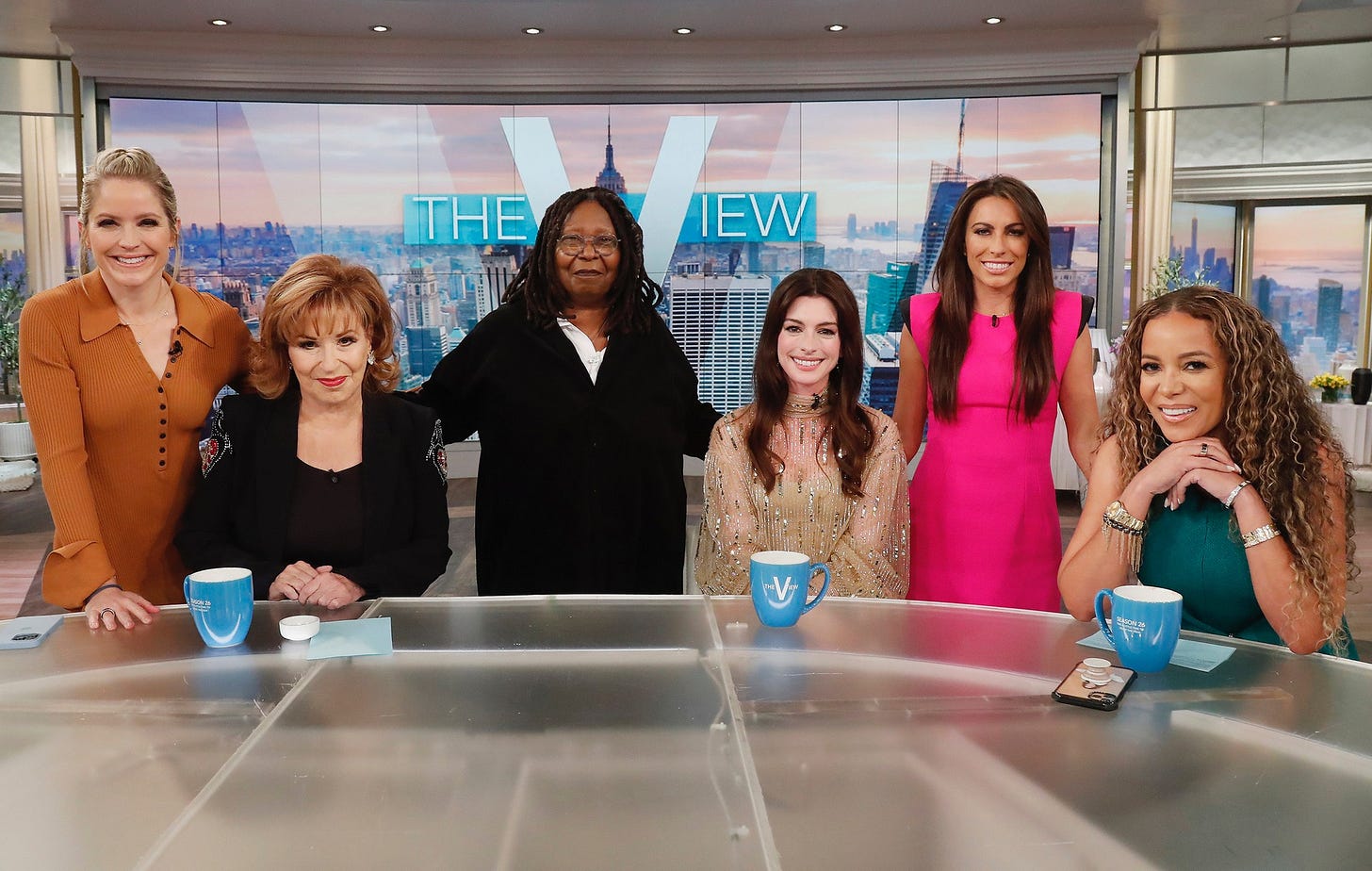

Actress Anne Hathaway recently appeared on The View, primarily for the purpose of discussing her new film Armageddon Time. But the discussion also touched on (or was forced to give way to) the matter of abortion.

Sadly, Hathaway showed little grasp of either the morality of abortion or the logic required to discuss it. She doesn’t realize it, but she’s aping her fraudulent lord, the Devil.

A crass rationale. It appears that Hathaway believes it's okay to kill unborn babies if the reason is to advance one's career and having a kid would just be too inconvenient. Hathaway tells the ladies:

When you’re a young woman starting out your career, your reproductive destiny matters a great deal.

Ironically, one of Hathaway’s most popular movies, The Devil Wears Prada (which I confess I enjoyed), conveys the message that there's more to life than raw career ambition. Other things matter at least as much, if not more.

Hathaway’s “justification” of abortion, then, actually implies that Miranda Priestly is the moral hero of the film.

“Reproductive destiny”? What does that even mean? Merriam-Webster treats destiny as a synonym for fate:

Destiny: “a predetermined course of events often held to be an irresistible power or agency”;

Fate: “the will or principle or determining cause by which things in general are believed to come to be as they are or events to happen as they do : DESTINY[.]”

Yet by evoking and defending “freedom of choice,” Hathaway is either just contradicting herself—or implying that “destiny” can be subject to human control, and that control is exercised by the power of choice.

That by itself is philosophically suspect, given that countless other factors can disrupt your plans so badly that your objectives are tossed into the flames of oblivion. Humans really don’t have ultimate power over their own destinies, though choice enables us to influence them.

Meaning simply that choices have consequences.

But our choices don’t only have consequences for ourselves: they also affect, for good or bad, other people.

Such as unborn babies.

“Not a moral conversation”? Throwing around a nebulous term like “reproductive destiny” is Hathaway’s vain attempt to evade the moral nature of the discussion she’s thoughtlessly waded into.

Consider the three choices available (in our society) to a pregnant woman:

Deliver and keep the child;

Deliver and give up the child for adoption; or,

Kill the child.

All of those are by nature choices involving morality that impact not only the baby’s life but the mother’s too.

Yet Hathaway absurdly claims:

This is not a moral conversation about abortion . . . . [T]his is a practical conversation about women's rights and . . . human rights and the freedom that we all need to be able to choose[.]

Look at the italicized words: she’s made a patently self-refuting statement. Her words are morally loaded:

“Practicality” begs the question as to whether or not an objective is worth achieving. Determining the worth of something is an inherently moral pursuit.

“Rights” can only exist in a moral framework: rights are what we, either personally or collectively, owe to others. And rights are mirrored by responsibilities. Both of these are, by nature, moral things.

“Freedom” presupposes a value-distinction between freedom and bondage. It’s related to rights in the sense that we are morally obligated to acknowledge and honor the freedom of others, as we would have them do for us.

But even more fundamentally, the above terms hinge on what it means to be a “woman,” or, deeper still, a human being. Whether or not a human being is “owed” anything, or “ought” to be granted “freedom,” begs such questions as: What kind of a being is a human—accidental or intended?; What is the meaning of human life—self-centered pursuit or something loftier?

These are all, unavoidably and unarguably, moral subjects! They presuppose a Moral Standard by which we discern what is our “right” and what is our responsibility.

That same Moral Standard also determines what is a legitimate freedom and what isn’t. We can reasonably argue that one is free—certainly morally and, it should follow, legally—to defend oneself. But one is not free to assault others. That’s a moral distinction between two kinds of freedom.

Ms. Hathaway, if you're addressing the abortion issue or human rights, you are having “a moral conversation,” whether you want one or not.

You can’t escape it.

And trying just makes you look foolish.

Mercy for…? Another moral issue is mercy, which you claim is at the heart of “women's right to choose.”

Abortion can be another word for mercy. . . . We know that no two pregnancies are alike, and it follows that no two lives are alike. How can we have a law, a point of view, that we must treat everything the same?

When you allow for choice, you allow for flexibility, which is what we need in order to be human.

This kind of puts us in the same realm as the phrase “reproductive destiny”: what does it even mean?

Strangely, Hathaway doesn’t specify the recipient of this “mercy” in her amoral, not-well-thought-out universe.

Abortion certainly isn’t mercy for the snuffed-out baby. It destroys in advance whatever she might have become in this world. And it robs the world of whatever that person might have contributed to it.

It puts both the mother and the abortionist in the Godlike position of judging whether or not another person’s life—a human life!—is worth preserving before it’s even been lived.

What presumption. What gall. What satanic self-idolatry.

Ironically, abortion isn’t “mercy” for Mom, either. It turns her into a child-killer. It puts her in the haunting position of having destroyed a fellow human being. Thus it places an immeasurable burden of guilt on her shoulders. Moreover, it destroys in advance whatever good things she might have experienced in raising that child—or even in giving her up for adoption.

Such “mercy” is a mutilation of the soul.

Real mercy, on the other hand, would help the mother in terms of resources and relationships for not only giving birth but also raising the child or finding her an alternative home in which she can flourish. Real mercy is applied to both Mom and baby.

Hathaway’s comments on The View tell me two things: she actually knows little or nothing of mercy—but desperately, desperately needs it in the Person of Jesus Christ. He died for our self-idolatry in order to have us experience ultimate mercy and fulfillment in our Creator.

†